United States Air Service

USAS HistorySummary 1917-1918 Lafayette Escadrille

N.124/Spa.124 1st Observation

1st, 12th, 50th, 88th 1st Pursuit Group

27th, 94th, 95th, 147th 1st Bombardment

96th, 11th, 20th 2nd Pursuit Group

13th, 22nd, 49th, 139th 3rd Pursuit Group

28th, 93rd, 103rd, 213th 4th Pursuit Group

17th, 148th, 25th, 141st 5th Pursuit Group

41st, 138th, 638th 3rd Air Park

255th. List of Aces

United States Naval Aviation

US Naval AviationUnited States Marine Corps Aviation

US Marine AviationAircraft

Nieuport 28

Spad VII

Spad XIII

Fokker Dr.1

Albatros D.Va

Fokker D.VII

Nieuport 28

Spad VII

Spad XIII

Fokker Dr.1

Albatros D.Va

Fokker D.VII

Website: Atlanta SEO

E-mail us

Building a World War One Aerodrome

Payne Field, West Point, MS

By David Trojan, Aviation Historian

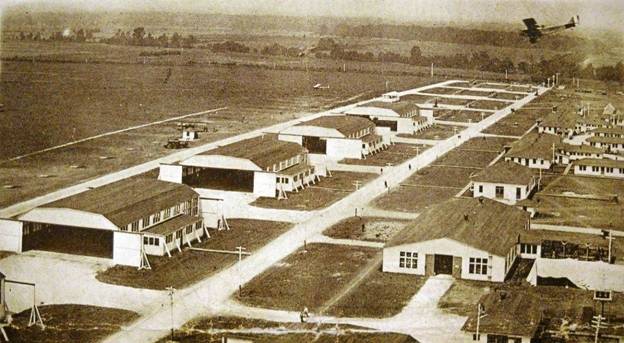

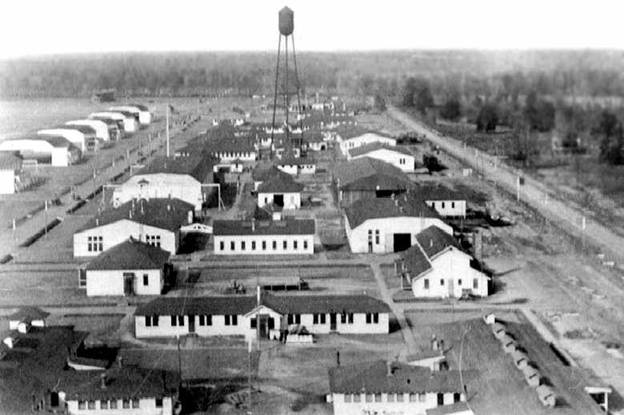

Looking Southwest

from the water tower at Payne Field, U.S. Signal Corps photo

[Note from Editor: the approximate location of Payne Field was here: Payne Field.]

During my travels around West Point Mississippi, I

was often asked what did Payne Field look like and is there anything remaining

there today. Payne Field was rapidly constructed more than 95 years ago and

stood for only a short time before it was torn down. If those hangar floors

could talk, what tales would they tell us? I wondered who built the base, how was

it constructed, what did it look like, and what happened to it all? I

researched these questions only to discover more than I thought possible.

The rapid mobilization effort for World War One included a massive demand for new flying fields that would support the nation's growing air power. In the beginning of WWI, there were only three military airfields in the U.S., but by the end of the war, there were almost 40. The airfield building campaign was on an unprecedented scale during WWI and Payne Field was one of fourteen primary flight training fields in America. How Payne Field came to be was typical of most airfields of the time. It took a good plan, capable workers and a dedicated individual to shepherd the process along.

The Construction Process

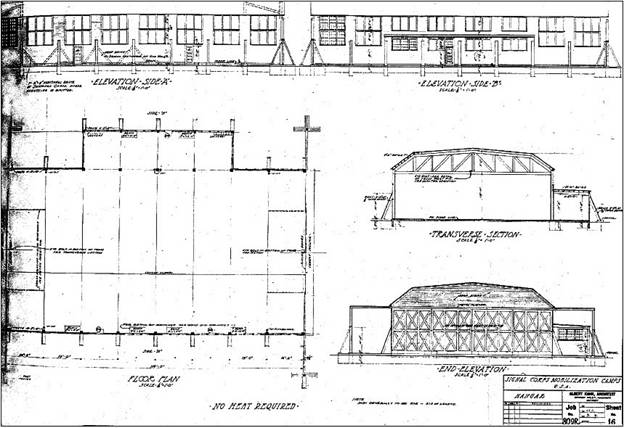

The July 1917 passage of the Aviation Act appropriated more than $50 million for Army aviation, with $13.5 million earmarked for construction of aviation facilities. This Act allowed the Army to procure land for aviation facilities without further legislative approval. The construction process remained essentially unchanged during the war, with the same people doing the same things under a series of changing administrative structures. The use of standard plans played an important role in maintaining this uniformity across the building program. In May 1917, the Signal Corps' Construction Division commissioned Albert Kahn, the designer of the Langley Field plans, to produce a standard airfield design. He finished this design in only ten days, generating a standard plan on a one-mile-square section that included 12 aircraft hangars and 54 other buildings meant to accommodate 100 aircraft and 150 student pilots. It was referred to as the Signal Corps Mobilization Hangar Plan.

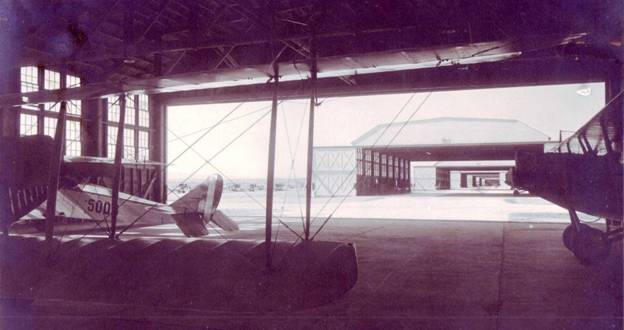

The hangar plan called for a 66 x 120 ft structure, two stories high of wood framing, wood siding, and asphalt shingle roofing. Bolted wood trusses formed a distinctive low pitched gambrel roof profile. The side walls were framed with stacked double sash windows to let in natural light and nine wood buttresses augmented each side of the structure. Affixed to one side was a center-placed flat-roofed frame wing used for workshops. The hangars had four massive 16-foot-long board-and-batten sliding doors that stood on steel rails and hung from a track that extended beyond each side of the building. The doors rightcolumnopened to the full width of the building by means of exterior door carriers. Inside the hangar, the walls were unsealed with the wood trusses exposed. The hangar floor was a concrete slab. The hangars were painted white and each could hold ten Curtiss JN-4 Jenny aircraft.

Signal Corps Mobilization Hanger Plan, USAF diagram

The airfield buildings were situated in a rectilinear arrangement along one side of the section, with the hangars in a row on the flight line and the remaining buildings in parallel rows behind them, leaving the rest of the section devoted to the landing field itself. This standard site plan, with 12 Signal Corps Mobilization Hangars, was implemented at many of the new flying fields established throughout the war. Although Kahn's standard plan directed the construction of most new airfields, a fair amount of leeway was granted the local constructing officials and contractors in their implementation. They were expected to conform to the plan unless they attained approval to the contrary, but the designs themselves were intended to be adaptable. Local topography and related conditions, coupled with differences in contractor, materials, and construction method preferences, could produce variations from site to site.

Kelly Field TX, 1920, Albert Kahn's standard airfield layout example, USAF photo

Most construction was executed by contractors, with a relatively small amount of work completed by Aero Construction Squadrons. The preferred form of contract changed over the course of the war, but a cost-plus-fixed fee type dominated overall. This contractual practice tended to be more expensive, but much faster. Early on, the contractors themselves were responsible for the procurement of supplies and materials at the local level, but the government took over the central control of material distribution when vital commodities began to be in short supply. Time was of the essence in the emergency construction programs, and cost-efficiency and fiscal responsibility was often sacrificed for the sake of speedy completion. Most contracts throughout the war were completed within a standard 60-day deadline, despite complications arising from labor, transport, and supply problems. The quality of the resulting construction was not generally high. Most fields received only temporary construction, with wood-framed buildings and wood or steel framed hangars, and most landing surfaces were of grass, dirt, or cinder.

The Five Waves of Construction

New aviation facilities were constructed in five general "waves" of building activity spread throughout the war. Each wave consisted of a number of facilities chosen for development at about the same time, and by the same administrative body. The first wave included those facilities that were already begun by the time the United States entered the war along with those sites chosen for development in the first two months of the war during May and June 1917. Five facilities were scheduled to continue the construction programs that had begun in early 1917. They included: Rockwell Field, CA (North Island); Langley Field (Langley AFB); Kelly Field (Kelly AFB); Chandler Field, AZ (Williams AFB); and Hazelhurst Field. Both Langley and Rockwell Fields largely abandoned attempts to continue permanent construction, opting for greater numbers of temporary hangars that were cheaper and easier to construct.

Five new airfield sites were selected for the construction during this initial wave. These fields were Selfridge Field, at Mount Clements, MI (Selfridge ANGB); Chanute Field; Scott Field (Scott AFB); Wilbur Wright Field, Dayton, OH (Wright-Patterson AFB); and Kelly Field 2 (Kelly AFB). By the middle of the summer of 1917, construction was already under way at the five new sites, under the control of the Signal Corps Construction Division.

The Signal Corps' first Site Selection Board was organized in June 1917. This Board identified the sites that would constitute the second wave of airfield construction.

The Site Selection Boards had little in the way of guidance regulations, they were simply small groups that toured sites prepared for inspection by local interests. Nevertheless, this system remained remarkably free of any hint of graft or corruption. Sites approved by the Site Selection Board, were forwarded to the Signal Corps Headquarters for endorsement, and then advanced to the Adjutant General's Office. There legal agreements were prepared, arranging for local contractors to erect the necessary buildings in accordance with standard plans provided by the Construction Division.

The first Board chose seven sites: Park Field, at Memphis, TN (NAS Memphis); Gerstner Field, at Lake Charles, LA; Carruthers Field, at Dallas, TX; Barron Field, at Fort Worth, TX; Rich Field, at Waco, TX; Call Field, at Wichita Falls, TX; Ellington Field, at Houston, TX (Ellington Field ANGB).

The third wave of new airfields was selected in the fall of 1917. They were all in the South and Pacific Coast regions, in an attempt to avoid the winter weather of the northern half of the country. The selected sites were: Brooks Field, at San Antonio, TX (Brooks AFB); Eberts Field, at Lonoke, AK; Taylor Field, at Montgomery, AL; Heistand Field, at Arcadia, FL; Valentine Field, at Arcadia, FL; Indianapolis, IN (motor speedway selected for Aviation Depot site). Bolling Field DC (Bolling AFB) was also acquired, but not by the Selection Board.

The fourth wave of airfield construction began in early 1918, as the third and last Signal Corps Site Selection Board began to select new locations. Flying fields that were selected during this wave included: Souther Field, at Americus, GA; Payne Field, at West Point, MS; March Field (March AFB); and Mather Field CA.

The fifth and final wave consisted of those facilities sited and constructed over the closing months of the war. Many of these sites were support facilities, especially depots, and some were not yet completed by the close of hostilities in November 1918. Five Aviation General Supply Depots, two Tran-shipment Depots, four Aviation Acceptance Parks, and a small number of flying fields were in this last wave. They included: Montgomery, AL,— Aviation General Supply Depot (Maxwell AFB); Fairfield, OH — Aviation General Supply Depot (Wright-Patterson AFB); Little Rock, AK — Aviation General Supply Depot; Dallas, TX — Aviation General Supply Depot; San Antonio, TX — Aviation General Supply Depot; Richmond, VA — Tran-shipment Depot; Middletown, PA — Tran-shipment Depot; Dayton, OH — Aviation Acceptance Park; Buffalo, NY — Aviation Acceptance Park; Detroit, MI — Aviation Acceptance Park; Elizabeth, NJ — Aviation Acceptance Park; Pope Field, at Fayetteville, NC (Pope AFB); Chapman Field, at Miami, FL; Love Field, at Dallas, TX.

In addition, a great deal of work was done, outside the immediate supervision of the Construction Division, on a complex of flying fields centered around Hazelhurst Field on Long Island, NY. These facilities included Damm, Brindley, Lufberry, Miller, Roosevelt, and Mitchel Fields. The vast majority of the construction completed in the five waves was of a temporary nature. Many of the fields were abandoned following the armistice in November 1918, and some ongoing construction projects were halted in mid-run.

Lease Agreement with West Point

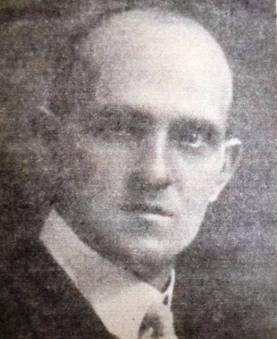

Mr. R. L. Betty, Secretary of the West Point MS Merchants'

Association, photo courtesy Bryan Public Library

Mr. R. L. Betty, Secretary of the West Point MS Merchants'

Association, photo courtesy Bryan Public LibraryMr. R. L. Betty, of West Point MS, was the principal person who secured the site location for Payne Field. On July 17, 1917, Mr. R. L. Betty, Secretary of the West Point Merchants' Association wrote the War Department requesting an investigation of West Point as a suitable location for an Aviation Training School. He received replies from the Signal Corps detailing requirements and stating that when favorable specifications were received, an inspector would be sent to investigate its claims. Mr. Betty made a quiet but careful investigation of all the sites available and reported back to the Signal Corps his findings. On Dec. 9th, 1917, Mr. Wm. P. Stevens from the War Department arrived to look into the claim. During his visit, the City of West Point offered several concessions in addition to the War Department requirements. After a review of the proposal and a tour of the sites, Mr. Stevens recommended that further study be made.

The Signal Corps Site Selection Board arrived at West Point on Jan. 12th, 1918 to conduct a final investigation. The board members included Lt. Col. Geo H. Crabtree, Major Benj. H. Castle, Major A. W. Peek, Capt. Boyreven, a French Officer, and Mr. Stevens. After a short conference it was decided to rely solely on one site for approval, as the others under consideration had objections not easily overcome. The main field site selected was 533 acres of land located on open prairie about four miles north of town and two auxiliary fields located nearby. The site chosen was ideal for aviation because it was located on a natural prairie, elevated above the surrounding area. The wind blows there even in the summer when just a couple of miles away there is no wind. This gave Payne Field a decided natural advantage over most airfields in America.

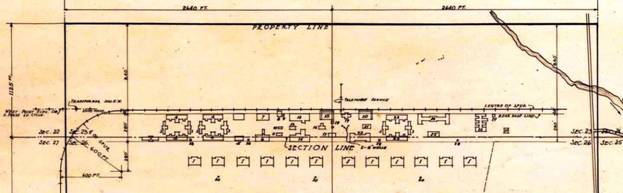

Payne Field map dated 11 Feb 1918

During a tour of the site, the Site Selection Board faced temperatures that stood at zero. A heavy snow covered the ground which had followed ten days of heavy rains and a blizzard during their site inspection. According to reports at the time "This inspection was made under the most unfavorable conditions." However, Mr. Betty received a telegram on Sunday, Jan. 13th 1918 from the Board requesting a contour map of the field. The map was immediately begun by Engineer L. W. Murphy and six assistants, but before map was competed, Mr. Betty received another telegram on Jan. 17th requesting that he come to Washington to complete a property lease.

Before leaving West Point on Jan. 18th, Mr. Betty secured an order from the Board of Supervisors agreeing to provide $15,000.00 to construct a cross section road and passed another ordinance authorizing $45,000.00 with which to furnish additional electrical equipment and to clear the land for the field.

Mr. Betty arrived in Washington on the 20thand stayed there one week to work out all the details and complete the lease agreement. On Jan. 23rd, Mr. Betty signed the lease and immediately arranged by telegram with R. V. Taylor in Mobile AL to construct the necessary railroads and locate a contractor to furnish a water supply line to the base.

Mr. Betty arrived back to West Point on Jan. 27th and faithfully began working with various committees on the base details. No time was lost in developing the plans and telegrams were used instead of letters to speed the work. Shortly thereafter, authority was received from Secretary of War to begin work on the public utilities at once and this was done immediately. George J. Glover, of New Orleans, La., was selected as general contractor, after which the rapid fire work began and the work of carrying out the many obligations of West Point. Excitement ran high as it had never run before in West Point.

The citizens of West Point co-operated splendidly with time and money whenever called upon, and every effort was made by the businessmen to comply with every requirement, none taking advantage of the rush.

The 500th Aero Construction Squadron

Officers from the 500th Aero Construction Squadron, #1 is Lt. William A. Coleman, Commanding, photo from NARA

Enlisted men from the 500th Aero Construction Squadron, NARA photo

Site construction was well under way by the time the 500th Aero Construction Squadron arrived March 20th, 1918. The contactor had completed building the road and rail network in preparation for the military construction men. An extensive system of drainage was also constructed at the site by contractors in an attempt to keep the airfield dry. The squadron consisted of about 140 officers and men. The 500th Aero Construction Squadron men were experts at building an airfield or aerodrome as it was then called. They had just finished Eberts Field, at Lonoke Arkansas before coming to Payne Field. When they arrived, no accommodations had been made for them and they had no place to live or eat. The unit slept on a train while they constructed their own living quarters. The men ate their meals out of doors from a field kitchen until a mess hall was completed in about a week.

The economy of the surrounding area was greatly helped by all the activity. For instance, Zula Gilmore (Mrs. B.Z. Dyer) and her family made lunches for the construction workers. Every morning more than 100 workers would come by their home to pick up a bag lunch with two sandwiches, cookies or fruit. When the post was completed, Mr. J.C. Bryan would send a wagonload of meat everyday to Payne Field. The proceeds from the sale of the meat are believed to have enabled Mr. Bryan to become Bryan Foods, at one time, West Points' largest employer.

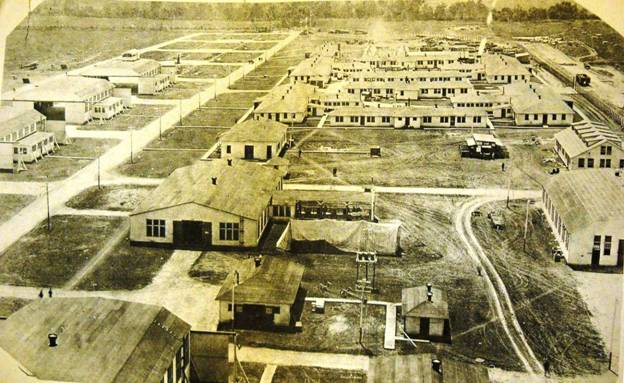

The rapid pace of construction continued at the base. It was documented "tell them what you want and the next time you come around you will find the accomplished result." A railroad line spur ran into the base to facilitate movement of construction materials. The 500th Aero Construction Squadron built the barracks, hangers; aircraft repair facilities, hospital, cold storage plant and warehouses. It was reported that the men in the squadron had pride in their unit and they took pleasure in their work that reflected good credit upon the Signal Corps. It was also reported that the men were "good soldiers and contented".

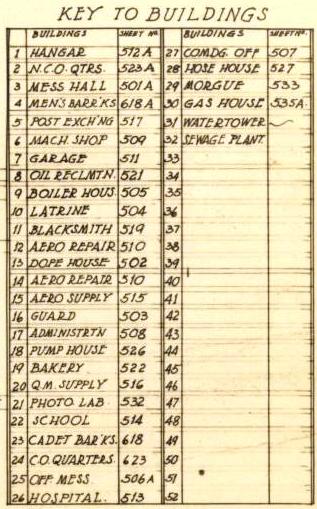

Payne Field site plan dated 11 Feb 1918 shows 12

hangars and numerous other buildings along with the rail line, map from the Canadian Centre for Architecture

List of buildings constructed at Payne Field

Upon his arrival at the new post, Lt. William A. Coleman, the senior officer from the 500th Squadron issued general order #1 assuming command of Payne Field. He was relieved on April 22 by Maj. Jack W. Heard, when he reported to the post as the commanding officer. The majority of the work was completed by May 1, 1918, but some construction continued until August. The men of the 500th Aero Squadron shipped overseas in October to become part of the American Expeditionary Forces. The total construction cost of Payne Field was $891,340.After its completion as many as 300 cadets at one time took the primary flight training course at Payne Field and over 1500 pilots graduated from there.

One of the mysteries of Payne Field is how did they build the base so fast? The site selected has ground made of a dense clay called "Gumbo" by local residents. It is very difficult to dig into and countless handles must have been broken off while trying. The movement of men and machines would have also turned the ground into a muddy sludge. Clues discovered at the site are the many horse shoes that have been found in the area. Using horse power and aided by a dedicated railroad line must have speeded the work. The builders were also motivated by the fact that there was a war on and they wanted to get the job done as soon as possible. The simplified plans and the experienced Aero Construction Squadron men certainly helped. They must have done good work because some of the original clay drainage pipes are still in operation today.

Payne Field was named in memory of Capt. Dewitt J. Payne. A native of South Bend, Indiana, Payne graduated from the University of Michigan in 1912 and from the School of Military Aeronautics at the University of Illinois. He was commissioned as a First Lieutenant and sent to a training field in Long Island, New York. Promoted to captain in October, 1917, Payne was then transferred to Taliaferro airfield in Texas. There, on February 1, 1918, Payne was flying JN-4D serial number AS-817 to aid a pilot who had crashed into the top of a tree. Capt. Payne crashed his own plane in the process and he died from the injuries sustained in the crash. The year following his death, the University of Michigan yearbook noted that the naming of the airfield in West Point, Mississippi, was "a fitting testimony of the esteem in which he was held as man, soldier, and flier."

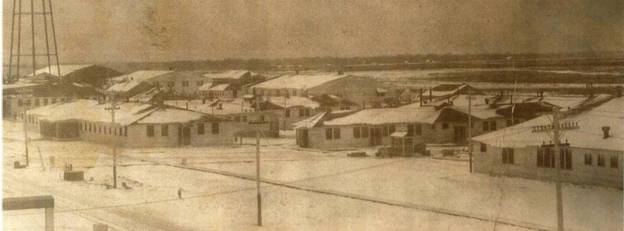

Pictures of Payne Field circa 1918

Looking west from water tower, U.S. Signal Corps photo

Looking southeast from the water tower, U.S. Signal Corps photo

Payne Field covered by snow during the winter of 1918, picture taken from the top of one of the hangars, U.S. Signal Corps photo

Aerial photo of Payne Field covered by snow 1918, U.S. Signal Corps photo

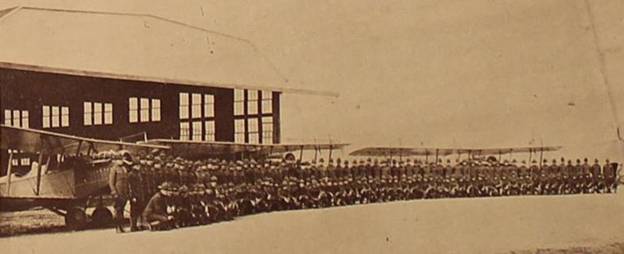

Squadron C in front of hanger at Payne Field, U.S. Signal Corps photo

Photo from a WWI Texas airfield shows

what it must have looked like at Payne Field, USAF photo from the collection of

the author.

A circa 1918 aerial view looking north at Eberts Field, Lonoke, AR(courtesy of the Lonoke County Historical Society & Shirley McGraw) Photo shows how similar the airfields were to each other.

End of the Era

With the Great War concluded, Payne Field was used for a short period as a storage depot before it was closed and all its assets were auctioned off in 1921. Farmers and builders came from all around to buy the buildings for their valuable lumber. Most of the buildings were torn down and carted away. The beautiful YWCA Hostess House was burned down. Anything left over was stripped by the local population for all kinds of possible uses including using the wood for heating.

The only things remaining today are the concrete foundations scattered over the land at the now over grown site. However, remnants from a couple of the buildings and hangars are still around today. A few locals always knew where their buildings came from. Nearly 100 years after Payne Field was built, at least two buildings are still in use, but not in West Point.

Three hangars, a mess hall, and Officer's Quarters were purchased by B. T. Clark from Dave Cottrell and Associates at auction in 1921, and re-erected in Tupelo. Mr. F. Hopkins and Sons Contractors from Meridian dismantled the buildings and moved them to Tupelo. The hangar buildings at 308 S. Broadway were used as cotton warehouses from 1921 to 1928. The building was then given a brick front and rear in 1928, but remains essentially the same building that was constructed at Payne Field. Different companies have occupied the buildings since that time including the International Harvester Co., D. W. Knox Buick Dealers, A. G. Bowen Chevrolet Co and Tombigbee Valley Electric Supply Co. Only one of buildings still stands today, occupied by the Reynolds Industrial Hardware and Supply Company.

Buildings made from Payne Field lumber, photo 1968 courtesy Daily Times Leader newspaper

Reynolds Industrial Hardware and Supply Company 308 S. Broadway, Tupelo MS, photo by Dave Trojan

Another building that is known that was built from lumber from Payne Field is the Gravlee Lumber Company building at 418 South Spring Street, Tupelo, MS. The infrastructure of this unique building was also once an airplane hangar, constructed of heart pine. It was also moved from Payne Field in 1922. It measures almost an entire city block at 27,000 + square feet.

Gravlee

Lumber Company building 418 South Spring Street, Tupelo MS,

photo by Dave Trojan

Wood timbers inside building at 418 S. Spring St., photo by Dave Trojan

Wood timbers inside building at 418 S. Spring St., photo by Dave Trojan

Less than 15 of the WWI mobilization fields continue to serve as permanent bases today, a reminder of the critical two years when American air power made its first great strides and established a network of ground facilities that would support its development over the following decaBrooks Field Texas that was constructed in late 1917 using Albert Kahn's design for a Signal Corps Mobilization Hangar. Hangar #9 at Brooks Field is the lone surviving example of this type. Hangar #9 was one of 16 constructed at Brooks and is recognized as the oldest existing wooden airplane hangar on a U. S. Air Force installation.

Payne Field site today

Aerial photo of the Payne Field site shows it completely overgrown where the buildings once stood. The flying field is now used for a catfish farm on one end and for cattle grazing on the other. Photo by Dave Trojan

Author Dave Trojan exploring the abandoned and overgrown site

Concrete slab was once a hangar floor,photo by Dave Trojan

Another hangar location photo by Dave Trojan

Hangar door rails, photo by Dave Trojan

Buttresses at the rear of a hangar, photo by Dave Trojan

Building foundations, photo by Dave Trojan

More building foundations, photo by Dave Trojan

Once upon a time this was the main road on the base, photo by Dave Trojan

Nearly a hundred years has passed since Payne Field was in operation and nature has done its best to reclaim the site. Payne Field is special and unique because so much about its history survives to this day. Its history just needed to be discovered by an Aviation Historian willing to mine the archives and explore the site to discover its historical treasures. Many documents about Payne Field survive to this day including: four large boxes of documents and photos in the National Archives; original copies of the airfield newspapers; and many photographs. Also unique is the fact that the main building site was abandoned and never developed. These make Payne Field unique in the history of World War One aviation training fields. It is hoped that somehow the site is preserved for future generations.

Au Revoir

By David Trojan, Aviation Historian

Biographical Information:

David Trojan is a Navy veteran who served 21 years as an Aviation Electronics Technician retiring in 2000. After retiring he became a government civilian employee (Tech Rep) at the Naval Air Technical Data and Engineering Service Command Detachment, MCBH Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii. While working on a Master degree, he focused on abandoned World War Two airfields and aircraft crash sites on the island of Oahu Hawaii as case studies in aviation archaeology. He has had the opportunity to travel around the country visiting over 250+ aircraft crash sites in 11 different states. During a temporary assignment to Mississippi, he extensively researched and explored a World War One airfield site that had been abandoned since the 1920s. During his investigations of historic aviation sites, he discovered that each site had a story to tell. His goal is to educate the public about aviation history and tell the stories that go with each case. He has written published articles for Naval Aviation Magazine, WW1 Aero magazine, Navy Times, and numerous newspapers concerning aviation archaeology. He has been featured on Armed Forces Radio and Television Network (AFRTS) during a visit to a historic military aviation site where he presented the Navy's policy on protection and preservation of historic sites. He has also given lectures to the Civil Air Patrol, FAA, Professional Pilots Associations, American Aviation Historical Society, and University students concerning aviation archaeology and aviation history. He is currently assisting the Travis AFB Heritage Center researching base history.

Learn more about the United States Air Service's 1st Pursuit Group:

Toul, Touquin,

Saints and Mauperthuis and Rembercourt,

"American Eagles" - 345 page illustrated history of US Combat Aviation in World War I

Events/Airshows

Events/Airshows

Events/Airshows

Pilots/Aviators

Raoul Lufbery

Raoul LufberyAce of Aces Eddie Rickenbacker

26 victories Quentin Roosevelt

Son of President KIA Frank Luke

18 victories in 17 days Eugene Bullard

1st African Am. Pilot David Ingalls

1st US Navy Ace List of USAS Pilots

Find a Relative American WWI Pilots

Mini bios

USAS Research

USAS Videos

Reading List

USAS Videos

Reading ListWWI US Aviation Related Links

WWI US Aviation Credits War Wings

by Phillip W. Stewart WWI Maps

Units & Airfields Payne Field

USAS Aerodromes now... USAS Archives

Questions? Need Help? American Expeditionary Forces

WWI Doughboys in France